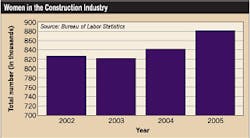

For many women-owned electrical contracting firms, the perception still exists that women-owned businesses are given preference when bidding on government contracts. This perception seems to hold true particularly in the construction industry, where although the number of women in the industry has been steadily increasing (Fig. 1 below), women currently comprise only 12% of the workforce (Fig. 2 below). This lingering stereotype also persists despite President Clinton signing the Small Business Administration Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 1994 into law, which dismantled the centralized federal program for certification of women-owned businesses (WBEs), according to the Congressional Research Service report, “Disadvantaged Businesses: A Review of Federal Assistance.”

In its summary, the report says it is the policy of the federal government to encourage the development of small disadvantaged businesses (SDBs) owned by minorities and women. However, SDBs are statutorily defined as small businesses that are owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals who have been subjected to racial or ethnic prejudice or cultural bias — and who have limited capital and credit opportunities. Under the Small Business Act, as amended, African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Native Americans are presumed to be socially disadvantaged. Other business owners — who do not belong to these racial or ethnic groups (such as non-minority women) — must establish disadvantaged status as individuals for participation in certain federal programs. In other programs, women and handicapped persons are defined as socially disadvantaged and are eligible for participation as long as they are also economically disadvantaged. Therefore, a woman-owned firm also must be economically disadvantaged to qualify.

“I don't get any of my work because I'm a woman-owned business anymore,” says Veronica Rose, master electrician and president and CEO of Aurora Electric, based in Long Island City, N.Y. “Every time I think they've changed something to make it a little tighter and a little better, it's been basically useless.”

Rose began her career in the electrical industry by joining the electrical apprenticeship program under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) program. She became one of the first three women to earn her master's electrician license in New York City. In 1993, after working for L.K. Comstock, Arc Electric, and Fischbach and Moore, she went into business for herself with Aurora Electric.

By 2000, she'd built Aurora Electric into a $9 million business, employing at least eight full-time electricians — many of whom were women — and using anywhere from 30 to 50 union electricians working in the field.

But working in New York, Rose couldn't avoid the economic downfall in the aftermath of 9/11. “It was horrible,” she says. “We had specialized in systems, and one of our largest clients was the Port Authority. So when 9/11 hit, we lost a lot our client base. But we're on the way back up. We've picked up a lot of work with the Transportation Security Administration and have been doing a lot at the airports on different high-tech security systems.”

The passage of the transportation bill in 2005, Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU), also has helped Aurora build itself back up, in addition to the money reallocated to New York.

This one's too small. Although Aurora's downsized staff of seven has been busy with several projects, such as a CCTV upgrade for the Port Authority Bus Terminal on 42nd Street in Manhattan, underground work at Battery Park City, and several smaller retail projects, none of these jobs has anything to do with Ground Zero. In fact, Aurora hasn't won any contracts for reconstruction work, despite promises of hiring women- and minority-owned local businesses for those projects.

“I've talked to the big boys building down there, and basically they're spending the money to get everybody together to say that they want to do it, then when they get us to participate and bid on jobs, they say ‘Ah, well you're not qualified here, your price is too high there,’” says Rose.

According to Rose, small businesses aren't getting the reconstruction contracts. “They're bundled that way to keep it that way,” she says. “They don't bundle them less than $10 million a project, so there's no way in hell a small business enterprise is going to be able to get the project.”

Rose offers an example of a $200,000 project she was considering bidding on. The contractor asked for bids from small businesses, but then also asked for a 25% bid bond. “I'm a small business, and they basically want me to give them a check for $50,000 at the time I bid it,” she says. “That's ridiculous.”

Rose posits that the contractors want to discourage small businesses from bidding because they feel it's more work and effort to deal with small businesses. “They'd rather disqualify as many as they can and say, ‘Look, we did a good faith effort. The only ones that could really compete are the big boys,’ ” she says. “But once the big boys get involved, they waive those requirements.”

This one's too big. Fort Worth, Texas-based Stanfield Enterprises, otherwise known as S&J Electric, has the opposite problem when it comes to bidding on public contracts. At more than $30 million in revenue last year and with more than $3 million in heavy equipment and 300 employees, S&J Electric no longer qualifies as a disadvantaged business, even though the woman who started it from scratch still owns it.

“We don't meet the criteria even though we're a woman-owned company,” says Edith Stanfield, founder and president of S&J Electric. “In a period, they set a limit at this much sales or less in order to qualify as a disadvantaged company.”

For some companies, there's also the matter of the owner's personal assets being taken into consideration. “That's not such a problem for me because I haven't taken much money from the company,” Stanfield says. “I've used it to grow the company. I think the limit is under $750,000 though, so even if you just own a house now, it's probably worth more than that.”

However, on large-scale projects, bigger businesses may be the only ones equipped to handle the job. Stanfield cites an instance of one contractor having to hire 50 smaller subcontractors to do the work one large firm could have completed on its own.

“The bad part about this is that the companies that need to fill some of these quotas need subcontractors that are big enough with the resources to do these jobs,” says Stanfield.

Ironically, it may be the size of the contracts awarded to a disadvantaged business one day that disqualifies the business from those same contracts the next. “The jobs are getting bigger and bigger, the costs are getting bigger and bigger, so naturally the sales are going to be bigger and bigger,” says Stanfield.

Whose wife are you? Stanfield got her start at a young age in the field with her electrician father who was working on the Rural Electrification Act project in rural Texas. Much later, with a background in engineering, Stanfield bought the company in 1985 from her then-employer when she needed a job that would support her family and realized he didn't have enough business to keep her busy. At the time, the move was a gamble. The Texas oil business was in the dumps, and banks were going bust. But Stanfield invested $5,000 and earned her master electrician's license.

“I was over 55 when I took my master's exam,” Stanfield says. “A lot of people at 55, both women and men, think their lives are over. This particular phase of my life was just beginning.”

To get the business off the ground, Stanfield took a lot of jobs no one else wanted, especially the jobs on weekends, holidays, and nights. “We took a lot of work in the mud and grime,” she says.

She also experienced the challenge of being a woman in a male-dominated field. “The first job I ever got was at the Dallas/Fort Worth airport, and it happened to be a night project,” she says. “They said, ‘It's a nighttime job. Who's going to supervise it?’ insinuating I wasn't able to get out at night or that my counterpart would be much better at doing it.”

When Stanfield started her company she had difficulty getting bank loans and bonding. She bought the building for the company with a personal credit card after she was turned down for a bank loan. “But as time goes on and they learn more about you, they forget all of this,” she says. “They're not thinking of you as a minority company: They're thinking of you as a company that is in the critical path, that got the job done, and that is the low bidder.”

The perception that Stanfield wasn't capable of running an electrical contracting company because of her gender persisted even after she'd completed jobs and built up the business. “I've been asked, ‘Whose wife are you?’ when I was representing my company and being the patent chief person in charge of everything,” she says. “That's a perception that has been built up over many years, and it has not gone away.”

Paying it forward. To try and counteract this perception, both Rose and Stanfield mentor other women starting in the electrical contracting industry. Rose is on the apprentice board for New York City's Local 3. The apprentice program pairs each new female apprentice with a female journeyman or master electrician. By working with an apprentice, Rose hopes she can encourage more women to stick with a career in electrical contracting. She says that women used to drop out of the program because of a lack of support. “The first time you had a problem, you might drop out if you had no one that you could call,” Rose says.

Although Aurora Electric now has only one woman electrician, Rose would like to hire more. She also offers career advice to other women. “As long as they're an apprentice, they're considered subordinate to a traditional journeyman electrician; therefore, if they're not a threat they stay employed,” she maintains. “As soon as they're making journeyman's money, that's where we lose the women because they're not getting the jobs. I tell them you've got to hook up with other women in the trade so you can succeed. Don't try to do it alone because the isolation will kill you.”

Stanfield also mentors women in the industry. She volunteers time to the Tarrant County Business Owners Association of Women, Fort Worth-based National Association of Women in Construction (NAWIC), apprentice programs, and other fund-raising activities. “If I can reach somebody and say, ‘Look, you can do this if you really want to, but be prepared. Get the facts and don't lie to yourself,’” she says. “You need not think that they're going to send you work just because you're a woman. That is a fallacy. They don't send you work because you're a woman. You're going to have to fight in the same arena that everybody else does.”

S&J Electric doesn't have a formal policy of hiring other women. “I give every bit of the credit of my company to my employees, but as far as choosing them because they were women, I didn't,” Stanfield says. “I wasn't looking to fill this or that kind of quota.”

Lynda D. Dodson, master electrician, has worked at S&J Electric for nine years. She says her hard work is appreciated and fairly compensated at the firm. In the past, while working for larger firms, she feels she experienced discrimination in the form of unequal pay. Surprisingly, she says things were tougher for her as a woman in the office than in the field.

“In the field, as long as you work, people look at that, not just ‘She's a woman, she needs an easy job,’ ” Dodson says. “It was actually easier for me in the field than in the office. When estimating, my pay wasn't up to normal. It is now, but back then it was a challenge.”

Sidebar: Paper Tigers

The first federal effort to directly support female business owners, or women-owned business enterprises (WBEs), was issued by President Carter in 1979. Executive Order 12138 was designed to discourage discrimination against female entrepreneurs and to create programs responsive to their needs, including assistance in federal procurement. Through the issuance of the order, the Office of Women's Business Ownership was established within the Small Business Administration (SBA) to negotiate annually with each federal agency a percentage goal for the awarding of federal prime procurement contracts to WBEs.

Under the issuance, from 1982 to 1992 the number and revenue of women-owned businesses grew at increasing rates that outpaced other small business sectors (see Table on page C28). According to data from the SBA, the number of women-owned businesses grew in every sector of the economy in which the type of business could be determined — from a low of 73.2% for retail trade to a high of 382.1% for wholesale trade. Revenue increases for women-owned businesses ranged from 53.2% in mining to the 742.3% experienced by manufacturing.

With the Women's Business Ownership Act of 1988, the promotion of WBEs was given statutory authority. Under the act, WBEs were defined as a small business that is at least 51% owned, managed, and operated by one or more women. The act also established a loan guarantee program administered by SBA to guarantee commercial bank loans of up to $50,000 to small firms (not just WBEs); created a National Women's Business Council to monitor the progress of federal, state, and local governments in assisting WBEs; and authorized grants to private organizations to provide management and technical assistance to WBEs.

Annual procurement goals for WBEs continued to be negotiated between federal agencies and the SBA under the original issuance, Executive Order 12138. That is, until President Clinton announced the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act (FASA) of 1994, which established a 5% annual goal for WBE participation in federal prime contracts and subcontracts. For most divisions of government, this was a severe decrease. For example, the Dept. of Transportation's (DOT) previous goal was around 10%. However, FASA did amend the Small Business Act to give WBEs equal standing with small businesses and small disadvantaged businesses (SDB) in the subcontracting plans of federal prime contractors.

However, additional legislation for the federal government's promotion of WBEs was contained in the Small Business Administration Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 1994, which codified the SBA's Office of Women's Business Ownership; established an Interagency Committee on Women's Business Enterprise to recommend policies to promote the development of WBEs; and restructured the National Women's Business Council as a bipartisan federal government council to the Interagency Committee, the SBA, and Congress.