It may not always make the neighbors happy, but sports lighting has become big business for lighting designers and electrical contractors

There’s never enough time in the day. To be more accurate, there’s never enough light. Americans want it all, from holding down jobs and raising families to attending school and enjoying what little free time they have, and in that juggling of work and play, it’s just not possible to do it all before the sun goes down. For the thousands of professional sports wanna-be’s and never-were’s, community sports fields are the only places where it’s possible to chase their dreams or hold on to what’s left of them. And thanks to those tight daytime schedules that so many keep, the hours after the sun sets are often the only time they can do it.

Yet those who place so much value on their ability to play recreational sports after dark are oftentimes the same people who don’t want their night skies littered with stray sports lighting. “Everybody wants the ball park near them, but nobody wants the light shining in their backyard at 11:00 at night,” says Rick Kohl, vice president of sales for Qualite, a Hillsdale, Mich.-based sports lighting manufacturer. Crowded residential suburbs—the areas that create the greatest demand for recreational sports complexes—tend to be populated by citizens most averse to light pollution, or the light that illuminates more than the structure for which it’s intended. This steady demand for well-lit parks with unobtrusive lighting has created a complex market for lighting designers who think they can provide just the right amount of light.

Batter up. When the Lawrence Parks and Recreation department in eastern Kansas undertook the project of building a four-field softball complex near Clinton Lake in early 1996, it didn’t have to contend with a neighborhood committee intent on blocking the installation of intrusive lighting; the area had yet to be developed. Instead, the main factor that would determine the amount of lighting necessary for the $2 million Clinton Lake Sports Complex was the level of play it would host.

The first criterion that determines lighting needs for a sports field is television coverage. Almost every professional sporting event is televised nationally or by local broadcast networks, requiring an intense level of lighting. National Football League stadiums require between 250 footcandles and 300 footcandles of illumination, calling for nearly 600 1,500W or 2,000W metal halide lamps.

However, barring expansion, there are only so many fields in professional sports, and most will go 20 years or more without substantial updates to their lighting systems. As a result, local fields, such as the Clinton Lake complex, make up the market in which the majority of sports lighting projects lie. By contrast, typical softball fields built for tournament play and Little League-sanctioned baseball diamonds require 50 footcandles of illumination in the infield and 30 footcandles in the outfield, calling for 20 to 30 of the same 1,500W fixtures used in professional stadiums.

Lawrence Parks and Rec wanted a design that allowed for future tournament play—standard play would require 30 footcandles in the infield and 20 footcandles in the outfield—but Bob Stanclift, the department’s adult sports supervisor, says not much thought was given to the idea that the park would host televised games.

A blueprint for bulbs. Once the level of illumination necessary is determined, the next step is finding someone to design the system. And if you’re planning on lighting a sports field, chances are you’ll eventually cross paths with Qualite or Musco Sports Lighting, Oskaloosa, Iowa. With a virtual lock on the sports lighting market, the two suppliers combine to install several thousand sports lighting systems per year. Although Lawrence Parks and Rec had used Musco systems at all of its fields in the past, it went with a Qualite installation at Clinton Lake. The sports lighting supplier provided the poles and fixtures, and Topeka, Kan.-based Latimer, Sommers & Associates designed the electrical system.

Although different levels of play require different-sized fields, dimensions for baseball and softball diamonds don’t vary drastically. As such, it may seem that a lighting design that works for one field will work for them all, but that’s rarely the case, says Don McLean, president of DMD & Associates, a Vancouver, B.C.-based electrical engineering firm that specializes in sports lighting design. “Some consultants use what I call ‘cookie-cutter’ designs,” he says. “But each project is unique. I wish we could cookie-cutter them out, because we’d be more profitable.”

Qualite’s Rick Kohl agrees. “You might say a baseball field is a baseball field,” he says. “But the facility dimensions always change. Where are the grandstands? Are there elevation issues? Sometimes ball fields are even designed inside of a bowl or have a high bank on one side that lends itself to seating.” These facility-specific dimensions and topographical anomalies can vary greatly from one field to the next and have a significant effect on the setback, or distance from the field, of the lights. The farther from the field the lights are located, the more light necessary.

With the necessary light level established and field dimensions considered, the rest of the design will begin to fall into place. Using computer modeling that cuts a field’s surface into virtual squares and estimates the amount of light that will hit each point on that grid, lighting designers can determine the number, location, and height of poles necessary to evenly distribute light over the entire field. These models will display the number of footcandles at each point on the grid, allowing designers to spot and adjust for variations in light levels.

Although it’s impossible to maintain the exact same illumination level across the entire field, the goal of a good sports lighting system should be to create an even transition between the lightest and darkest areas of the field. Playability and the safety of the players can be adversely affected—particularly in baseball and softball—if the ball travels through drastically different areas of light. The difference between the highest and lowest light levels is called the max/min ratio. A field with a maximum light level of 35 footcandles and a minimum of 24 footcandles, for instance, will yield a max/min ratio of 1.46. Lighting with a ratio of 1.5 or lower is perceived by the eye as perfectly smooth. Ratios of 1.5 and 2.0 are good, but playability and safety begin to decline sharply as the ratio approaches 3.0.

An additional consideration in any design is the “burn-in” time. The metal halide lamps used in sports lighting installations will burn brighter—as much as 20%—for the first 100 hr of use. In order to provide the appropriate maintained light level, or the level achieved once the gases in the arc tube settle and the initial brightness wears off, a proper lighting design should account for this eventual decrease. In fact, companies like Musco and Qualite recommend designing the system with an initial brightness 25% higher than the desired maintained level to allow for other factors like dirt accumulation on the lamps. As a result, a field that requires a maintained level of 30 footcandles will oftentimes need to be designed with an initial illumination of 37.5 footcandles.

The field is your canvas. The poles and fixtures are the two most important parts of any sports lighting design. If you think of a sports complex as a canvas, they work together in a well-designed system as the brush and paint, respectively, to paint the field in light.

The function of the pole doesn’t change much from one supplier to the next. Its job is to support the lights above the field in an array that will effectively distribute the light. However, the height of the pole is critical. Most communities place a standard 60-ft restriction on pole height for aesthetic reasons; they may not be visible at night, but tall metal poles sticking out of the ground can disrupt the skyline during the day. Within those restrictions, lighting designers must choose the correct combination of lamps to evenly spread the light without coloring outside the lines of the field, so to speak.

To make that possible, companies like Qualite and Musco will use anywhere from five to seven different beam shapes—some round, some oval—to create the right combination. Sports lights are designed much like a flashlight: mirror-like reflectors line the inside of the fixture, reflecting the light emitted by the lamp and concentrating it into a single beam. The strength and width of the beam can be altered by adjusting how far the lamp is sunk into the fixture.

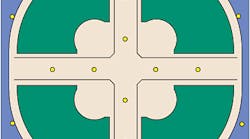

To meet the tournament level specifications required for the four fields at the Clinton Lake complex, Latimer, Sommers & Associates settled on a 16-pole design that supports 135 1,500W fixtures. The fields, which back into one another to create a circular design, each use two poles in the outfield and share four more with the fields adjacent to it (Figure).

Raise high the light beams. What happens when a field isn’t lit properly and the light spills on to neighboring property? Light pollution has become a major point of contention between local sports complexes and the communities they serve. Unlike air and water pollution, it doesn’t threaten to punch holes in the ozone or poison lakes and rivers. Instead, it’s a problem that can only be quantified by the amount of visual discomfort it causes for those subjected to it.

Light pollution exists in three forms: glare, light trespass, and sky glow. Glare is the bright direct light created by poorly aimed fixtures, most commonly affecting players and fans. Light trespass refers to the light that spills outside of the boundaries of a sports field and illuminates neighboring yards or houses. Sky glow is light that travels up and illuminates the sky instead of the field, making it difficult to see stars.

Doug Snyder, a retired electronics engineer, moved from San Jose, Calif., to Bisbee, Ariz., a small city along the U.S./Mexico border, to pursue amateur astronomy, only to find that several nearby sports fields were flooding the night sky with light. Unable to enjoy the stars like he thought he would, he began to devote an equal portion of his time to petitioning the local city and county boards to improve lighting ordinances.

“Cities nearby have quite an establishment of sports fields,” he says. “Once the plans for a new field are approved by the city, most of those complexes use the cheapest lighting fixtures available. Generally, they’re unshielded and they direct most of their light across on to neighboring properties.”

The International Dark Sky Association (IDA), whose mission to preserve the natural beauty of the night sky isn’t nearly as ominous as its name suggests, is the group that speaks for people like Snyder. Located in Tucson, Ariz., and made up of astronomers and lighting engineers, the IDA has encouraged local municipalities to adopt the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America’s (IESNA) recommended practices for outdoor lighting, which include sports field lighting requirements. Nancy Clanton, the president of Boulder, Colo.-based lighting design firm Clanton & Associates and a member of the IDA’s board of directors, understands the need for lighting at sports fields, but is worried about the consequences. “We keep adding light, but nobody ever takes light away,” she says.

The IDA doesn’t want to do away with nighttime sports, but it wants to make sure owners of local sports complexes take the necessary steps to prevent light trespass and sky glow. Measures like using higher poles, which allows light to point down at the field instead of at an angle and toward neighboring houses, can have a dramatic effect on light pollution. Although many communities frown upon taller poles, Clanton believes when weighed against the reduction in light trespass they would create, the appearance of the poles in the daylight will become less of a concern.

Lighting suppliers are also doing their part. Musco and Qualite offer internal louvers and visors that shield the light and prevent it from spilling beyond the boundaries of the fields.

The western edge of Lawrence, Kan., where the Clinton Lake complex is located, has few houses, but that’s beginning to change. Developments are popping up east of the fields, creating the potential for future light pollution issues, but Bob Stanclift isn’t worried. He says visors were written into the design to head off concerns of light trespass before they happened. In fact, the complex has only received one complaint so far, but it was about a parking lot light. And if that’s the worst of the complaints, Lawrence’s weekend (and weeknight) warriors will no doubt continue to flock to the diamond after dark. EC&M