Satina Matthews didn’t know it before showing up to work that morning in July 2014, but it would be her last day at the Truland Group. Hers wouldn’t be an isolated termination, though. Virtually all of the nearly 1,000 people employed by the electrical contractor based in Reston, Va., located just west of Washington, D.C., would receive pink slips as well. And within days, on July 23, the century-old business that had generated half a billion dollars in annual revenue in 2012 and another $450 million the following year would file for bankruptcy.

Despite its longevity and the appearance of success, there would be no General Motors-style restructuring of debt that would allow the scuffling contractor to find its footing and re-emerge stronger and more financially stable. According to its first-day filings in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in the Eastern District of Virginia, the Truland Group was more than $27 million in debt, and, as it would be revealed during a hearing two weeks later, the company had just $1.3 million in the bank. “It was truly an implosion of the classic sort,” a lawyer for Truland’s bankruptcy trustee told a federal judge at the time. This was a Chapter 7 filing — a total liquidation. Everything had to go, including the company’s considerable workforce, which was spread out among offices around the D.C. area and job sites across the country.

The shuttering and subsequent bankruptcy weren’t complete surprises; rumors of liquidity issues had been spreading, fanned primarily by a stalled project for the National Security Agency for which Truland was owed $50 million. But that didn’t make the mass layoff on July 21 any less shocking. In fact, Matthews’ termination — along with those of everyone else at the electrical contractor — wasn’t just abrupt. It was potentially illegal. So on July 30, less than two weeks after being shown the door, Matthews and a fellow employee, Summer James, sued Truland in bankruptcy court. Their claim? That their employer had failed to give them enough notice before the layoff. But they weren’t just fighting for themselves. They were acting on behalf of every other Truland worker who’d been abruptly axed.

Heads up

In July 1988, after a multiyear battle, the U.S. Senate and Congress passed the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act. A response to numerous plant closures that had rocked the rust belt in the mid-’80s, the WARN Act’s intent was simple: to give employees the courtesy of a heads up well in advance of a mass layoff. “It is the concern of the American people,” said Howard Metzenbaum, the Democratic Senator from Ohio who sponsored the legislation. “It is an indication of their fairness and their concern and their compassion and their willingness to treat workers who have given of their bodies and themselves over a period of years to give them notice when the plant is closed.”

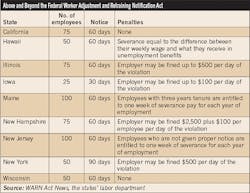

The version of the bill that became law — without, it’s worth noting, former President Ronald Reagan’s signature — was a shadow of what Metzenbaum had envisioned. One year earlier, he had introduced legislation that would require a business to provide its workforce 90 to 180 days’ notice prior to a plant closure or mass layoff, depending on the number of employees affected. In the end, Democrats and Republicans settled on something much more favorable to business owners: Employers with at least 100 full-time workers must give 60 days’ notice prior to a facility closure or layoff that would affect at least 50 employees. And although several states have enacted their own stricter WARN statutes (see Table), the federal act’s provisions haven’t changed in nearly three decades.

And so it was the WARN Act Matthews and James were relying on when they filed a class action lawsuit against Truland in July 2014, with the hope of including every eligible former employee of the contractor. The pair declined to comment for this story, but their attorney, Charles Ercole, with the law firm Klehr Harrison Harvey Branzburg, offered insight into the state of mind of the typical plaintiff in a WARN case.

“I’ve represented employees in more than a dozen mass-shutdown cases,” he says. “And I’ve seen people lose their houses, lose their cars, and not get the medical attention they need because they’ve lost their health care coverage. That’s not to say that some of those issues might have not still existed. But in these cases, it becomes an emotional issue in addition to the financial hardship.”

Numbers on WARN cases are elusive. The federal government doesn’t require companies to report when they initiate a mass layoff, even if they’re following the law and giving their employees the proper notice. (States do require reporting, but navigating 50 departments of labor, each with its own byzantine Freedom of Information Act rules is so onerous that even those who specialize in WARN litigation don’t bother trying.) Short of combing through court documents in every jurisdiction, data on lawsuits is sparse. As a result, it’s almost impossible to determine how often they’re successfully litigated. That said, John Philo, legal director of the Maurice & Jane Sugar Law Center for Economic & Social Justice, which represents employees in WARN cases, estimates there are more than 100 such suits per year. “Realistically, though,” he says, “it’s really hard to put your finger on.”

For Matthews and James, though — no matter how open and shut their case may have seemed — it was too early to begin speculating on their chances of victory last July. Within six weeks of the filing, attorneys for the Truland estate’s trustee filed a motion to dismiss the suit. According to the briefs, the trustee, Klinette Kindred, “appreciates the impact on all of these loyal employees and their families who were abruptly terminated just days in advance of the filings. … Employee creditors should file claims through the clerk’s office, and they will be addressed through the proof of claim process.” In other words, the pair, along with every other Truland employee affected by the layoff, needed to get in line behind the hundreds of other creditors who had money coming their way.

Take a number

With respect to Senator Metzenbaum and his efforts three decades ago, the WARN Act is, essentially, toothless. When the bill was originally written in the late ’80s, there was a large industrial component to the American economy. A single factory could employ hundreds, if not thousands, of employees. But today many corporations have decentralized, spreading their workforce out over several facilities, thereby reducing the number of employees at any one place — and consequently reducing their WARN liability.

Not only that, there are no double damages assessed if a company is found to have violated the law. And there are no punitive measures — no potential for incurring fines. The only thing laid off employees like Matthews and James are entitled to is 60 days’ worth of wages, and in many cases — particularly if the employer is financially strapped and filing for Chapter 7 — they may only get pennies on the dollar.

And yet, at least from the perspective of the employer, following the letter of the law would seem to present the fewest problems. As the saying goes, “You don’t just go into bankruptcy; you plan it.” So give the 60 days’ notice — and more often than not a faltering company knows it’s going down the path of liquidation long before it files — and you’ll only be paying your employees until the day you go out of business. Wait until the day you file, and you’ll be paying them an extra 60 days’ worth. “I think there’s an element of wishful thinking,” Philo says. “They say, ‘Let’s not act too quickly because something may come along and save us.’ Maybe they’ll get a line of credit or financing. But that’s tremendously misplaced.”

Jack Raisner, a partner in the New York office of Outten & Golden and a frequent representative of plaintiffs in WARN cases, is more willing to cut employers slack. “There are all kinds of rationalizations for not paying the employees,” he says.

Companies that find themselves in a death spiral and striving to stay afloat are preoccupied and may not have the presence of mind to start dealing with WARN when it’s something that they can leave to the bankruptcy trustee to try to mop up. “So there’s sort of a resistance, an inertia, an ‘It’s not my front burner concern’ attitude within distressed companies,” he says.

It’s still too early to say what was going through the minds of the Truland Group’s executives in the months preceding its bankruptcy, but there’s no disputing they failed to give proper notice. In opposing Matthews and James’s suit, the trustee made no attempt to argue otherwise. Instead, Kindred, through her attorneys, argued that the laid-off employees were only entitled to what’s called “wage priority.”

In bankruptcy cases, there’s what’s called a waterfall of payments, assigning priority to everyone owed money: First you’ve got secured creditors, which include the bank that loaned you money for your company’s building. Then there’s administrative priority, which applies to the lawyers, the accountants, and anyone else who runs the company as it winds down. Then come unsecured creditors — subcontractors, for example — and your employees. In other words, not only did the trustee’s attorneys believe Matthews, James, and all of their coworkers should get in line, but they also believed the employees should go to the back of the line — a place where they were much less likely to recoup any of their wages.

A happy ending

Given the difficulty plaintiffs have in prevailing in a case even as seemingly clear-cut as Matthews’ and James’, many employee advocates agree the WARN Act is ripe for strengthening. “The most immediate thing, in terms of strengthening, is the idea of scaling,” says Philo of the Sugar Law Center. “Sixty days’ notice just isn’t enough time if you have a thousand employees. And to be fair to employers, it’s hard for a company that barely meets the threshold of 100 employees, to offer even that much notice.” As a compromise, he suggests establishing a sliding scale, depending on the size of the company.

In fact, Raisner, the lawyer with Outten & Golden, helped to produce a report for Congress in 2008 on the merits of strengthening the act. At the time, Sherrod Brown, a Democratic Senator from Ohio (WARN’s birthplace) was introducing legislation that would increase the mandated notice time. Its companion bill passed the House of Representatives but never made it out of committee in the Senate.

As it turns out, Matthews and James didn’t need the law to be strengthened. On the day before Thanksgiving, Judge Brian Kenney issued his ruling on the Truland trustee’s motion to dismiss, finding in favor of the plaintiffs: Not only would their suit be allowed to move forward as a class action, but should they prevail, their claim would also be granted administrative status, placing them ahead of other unsecured creditors. In addition to that, there will be no cap on the amount of wages they can recoup.

Typically, when employees are relegated to wage priority status in bankruptcy cases, they may only collect $11,725 per person. While Ercole says he doesn’t believe Matthews and James would have made that much in a two-month period, the lack of a cap will still be beneficial to the hundreds of unionized electricians who would. “This is a tremendous ruling,” he says. “It will really change the WARN landscape if more judges make similar interpretations.” The case is still months from being decided, but the two sides will meet for a hearing in July.

While the Truland mess offers insight into the protections — and, if you’re an employer, the responsibilities — the WARN Act creates, there’s another important takeaway for a company that finds itself in a similar situation. It’s a guideline Art Carter, a labor lawyer with Littler Mendelson, sums up succinctly: “Consult with qualified bankruptcy council and specialists in other areas to determine a pre-filing strategy and approach.” In other words, employers, you’ve been put on notice.

Halverson is a contributing writer based in Seattle. He can be reached at [email protected].